Telemedicine in Colorado

While many predictions from The Jetsons have yet to come to pass, their high-tech vision of health care is moving closer to reality, and it has gotten a boost from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has forced a rapid and monumental shift in how health care is delivered.

Over the course of two months, state and federal leaders have established telemedicine — or delivery of clinical care services between different locations via electronic exchange of medical information — as the new norm for health care during the state of emergency.

And it makes sense. Telemedicine ensures a safe distance between clinicians and patients. It allows patients to receive care without leaving home and allows clinicians who may be self-isolating to continue practicing.

Decisions to expand telemedicine — and the health care system’s swift “adopt and adapt” response — have big implications. How does telemedicine affect access to care, utilization, quality, cost, and satisfaction? It is a swiftly evolving field. Existing evidence of telemedicine’s impact is mixed and was produced in a pre-pandemic world.

Published research has found that telemedicine — and telehealth more broadly — largely meets or exceeds patients’ expectations of convenience and quality. Many providers, however, still prefer in-person visits. Telehealth is effective for monitoring and counseling patients with chronic conditions, as well as for psychotherapy. Telehealth shows promise for improving mortality and quality of life and reducing hospital admissions.

The jury is out on whether telehealth increases utilization or spending. It generally increases access to care, though some direct-to-consumer telehealth programs increased total visits instead of replacing in-person care. Other models of telehealth, such as e-consults between clinicians, show promise of savings. And researchers advise that any analysis of expenditures should start with the question “spending by whom?” Patients? Payers? Providers?

Ultimately, all questions inform whether this technology is adding value.

For example, many patients are finding value and convenience in the 150-year-old technology of an old-fashioned phone call with their doctor — a service for which many payers are reimbursing during the emergency. But will this popular mode of telemedicine ultimately improve health and decrease costs?

The billion-dollar question is whether Colorado is headed to a Jetsons-like future — or whether it will return to the recent pre-COVID-19 past after the pandemic passes.

The Policy Flurry

In responding to COVID-19, an alphabet soup of state and federal agencies quickly took steps to accelerate the use of telemedicine. The Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF) applied for a federal waiver to make telemedicine easier in long-term care facilities. The Governor’s Innovation Response Team and Office of eHealth Innovation — in charge of leveraging technology to fight the virus — moved quickly to fund telemedicine access across the state and make it easier for health information exchanges to accommodate telehealth infrastructure.

And many agencies issued regulations and guidance in March and April aimed at payers, providers, and patients. This brief focuses on the potential impact of these changes on all three groups.

Nationally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth benefits in Medicare, and the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) said it would ease enforcement of restrictions on sharing protected health information.

In Colorado, HCPF first announced telemedicine changes to Health First Colorado — the state’s Medicaid program — on March 20, and Gov. Jared Polis issued an executive order to expand telemedicine on April 1. Following the executive order, the Colorado Division of Insurance (DOI) and Division of Professions and Occupations each issued regulations and guidance.

These policy changes share three common characteristics. First, of course, is that they are aimed at accelerating the use of telemedicine in the wake of the pandemic. Second, each expands telemedicine by addressing pre-COVID-19 state or national restrictions. Third, the regulatory changes are intended to be temporary — only during the state of emergency or for a limited time after.

This last point means that decisionmakers will be faced with choices about whether to keep these adaptations once the emergency is over.

At the center of the discussion are big expansions of telemedicine policy including reimbursing Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), and Indian Health Services (IHS); reimbursing for telephone-based visits; and allowing video visits over apps like Skype or Facebook Messenger that do not comply with patient privacy laws.

Policymakers must balance competing demands of responding to a public health emergency, increasing access to health care, working within a constrained budget, and maintaining quality and safety.

In this brief, CHI identifies five strategic policy areas that federal and state leaders have targeted to expand telemedicine.

CHI has summarized the five areas with the acronym RAPID:

Reimbursement

Access to services

Professionals

Information

Definitions

This brief outlines key questions and research opportunities that will guide policy discussions in all five areas after the pandemic passes — whenever that is. It also offers an on-the-ground look at four health care organizations around Colorado that have expanded their telemedicine services during the pandemic.

Tele-terms

Telemedicine typically refers to the delivery of clinical care services between different locations via an electronic exchange of medical information. This definition is the focus of this brief.

Telehealth often refers to a broader scope of remote health care. In addition to clinical care, it can include patient and professional health-related education, public health, and health administration. For reference, the definition of telehealth in state statute is included on Page 18.

Asynchronous/store-and-forward telehealth refers to transmission of medical information such as X-rays or electrocardiograms between health care providers or between patients and their providers.

E-consults refer to asynchronous, provider-to-provider communications within a secure platform. Often, primary care clinicians will use e-consults to seek guidance from a specialist about whether a patient requires a specialist referral or can be treated in the primary care setting.

ECHO Colorado (Project ECHO): Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) is a collaborative model of medical education and care management. Virtual tele-mentoring sessions link specialists and community-based health providers, including in rural, frontier, and underserved areas.

PROFILE: DENVER HEALTH

Colorado’s Largest Safety Net Hospital Launches Telehealth Program in Weeks

In 2019, when Denver Health reviewed its telehealth program, none of its medical visits were being conducted remotely.

By April 6, 2020, 73% of adult and pediatric primary care visits at the state’s largest safety net hospital — which includes a network of FQHCs — were being conducted remotely. In some health care specialties, between 80% and 100% of visits were telehealth visits.

Ann Boyer, Denver Health’s Chief Medical Information Officer, described this rapid shift as a “great forced learning experience” in telehealth — one that revealed new opportunities for connecting with patients.

Not all health services can be delivered remotely. Denver Health has created a triage system to help identify which patients need to come into the hospital or doctor’s office and which can be effectively treated remotely.

As of late March, most visits were being conducted on the telephone. Transitioning to phone visits, which were newly covered by Medicaid and some other insurers, was the fastest and most accessible option. The hospital’s video visit platform had only been used by a few behavioral health providers before the pandemic. At the same time, some patients don’t have internet or a device that could access a video platform, and video platforms had more barriers to working with translators.

But the system was working to expand its video visits, especially for services like physical therapy or occupational therapy that can’t be reimbursed if they are delivered over the phone.

Doctors’ and patients’ experiences with telehealth tend to improve over time as people get more used to the approach. “There are growing pains,” said Haddas Lev, Denver Health’s Administrative/Operations Director for Ambulatory Care.

But telehealth visits can be even more accessible than in-person visits for people who might have trouble leaving work for long periods of time or finding transportation to the doctor’s office. “There are some patients who have a really hard time getting to their appointments, who have high no-show rates, who could really benefit from having an at-home visit with their provider,” Boyer said.

Lev said telehealth could allow the hospital to expand its capacity to offer treatments in areas where physical space was the limiting factor, and that eventually patients might be able to visit Denver Health doctors from whichever clinic is closest to their home using remote technology.

After the state’s social distancing policies change, “what we do will be largely dependent on what the policies say we can do,” Boyer said. “But giving options to patients is a nice thing.”

Reimbursement

Perhaps the strongest way to encourage telehealth is to expand the range of services for which public and private insurers will reimburse providers. This brief devotes extra time to this topic.

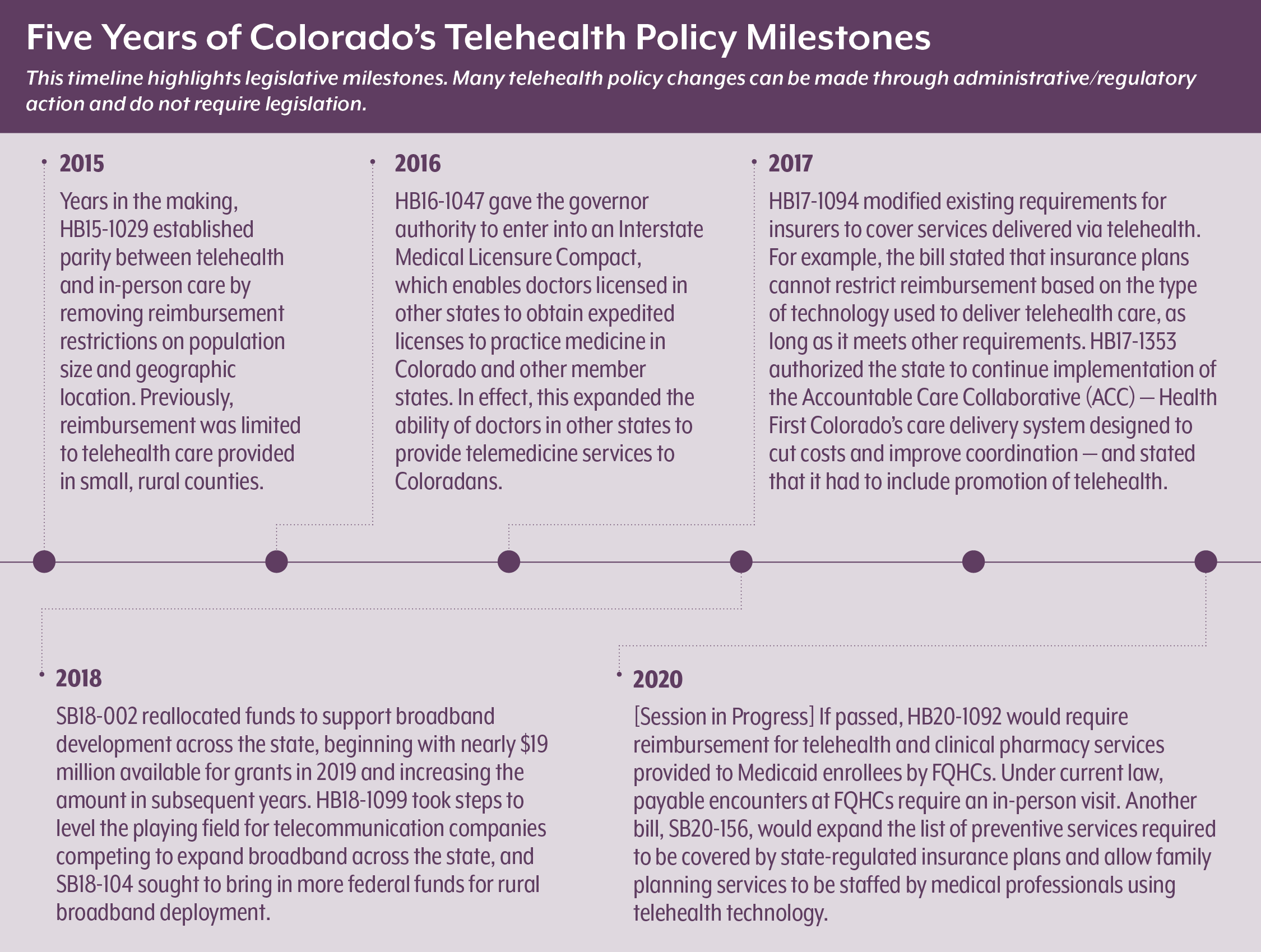

Colorado was already operating at a relatively high baseline for covering telehealth services compared with other states. In national comparisons, Colorado is considered progressive among states for making strides in telehealth. One big step was enacting legislation in 2015 mandating that telemedicine services be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person services. Policy experts often refer to this as “telehealth parity.” (See Colorado’s most recent telehealth policy milestones timeline on Page 7.)

The state’s emergency rules in response to COVID-19 went even further. When combined with policy decisions made by the federal government for the markets it regulates — namely Medicare and self-insured employer plans — most Coloradans were impacted in some way.

To give an idea of how many Coloradans are affected, the major recent telemedicine reimbursement changes below are broken out by the percentage of Coloradans covered according to the 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS):

Medicare (14%): The Medicare program significantly expanded telemedicine services in mid-March, setting the tone for state expansion. Colorado’s agencies mirrored many of Medicare’s approaches, such as reimbursing for telephone and chat, expanding the list of services covered, and allowing FQHCs and RHCs to be reimbursed. Medicare also started reimbursing for some types of asynchronous telemedicine.

Medicaid/Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+) (20%): Prior to COVID-19, Colorado’s Medicaid and CHP+ programs — which largely cover families and individuals with limited incomes — already reimbursed for many medical and mental health services delivered via live audio/visual connection, and for remote patient monitoring for individuals with some chronic conditions.

The COVID-19 state of emergency brought about alignment between HCPF and Regional Accountable Entities (RAEs) in tele-behavioral health billing policies. It also brought about three big changes for Medicaid and CHP+.

First, Medicaid and CHP+ expanded the types of telemedicine services — such as pediatric behavioral health, speech therapy, and physical therapy — that are eligible for reimbursement. Second, the programs expanded what counts as telemedicine to include telephone and live chat. These two approaches are discussed in the Professionals and Definitions sections.

Third, HCPF now allows three types of safety net providers — FQHCs, RHCs, and IHS — to bill for telemedicine visits. Prior to COVID-19, rules limited the payments to these providers to face-to-face medical encounters. Coincidentally, state lawmakers had already proposed legislation in 2020 — prior to the pandemic — attempting to change this. See timeline on Page 7.

Individual insurance (7%) and small group/large group markets (20%): These types of insurance are regulated by DOI. In March, DOI mandated that insurers offering plans in these markets cover all telehealth services for COVID-19 with no cost sharing to the patient.

After the governor’s executive order on April 1, DOI aligned the commericial market with medicare and medicaid guidance: reinforcing the types of services — such as behavioral health services, speech therapy, and physical therapy — that insurers are required to cover; expanding the modes of telehealth, such as telephone and chat; and reinforcing parity of reimbursement between telehealth and in-person services. DOI also required carriers to cover out-of-network COVID-19 treatment and other emergency services.

Self-funded employer-sponsored coverage (an estimated 30%): Self-funded employer plans — where employers themselves serve as insurers — fall under federal jurisdiction. To date, federal guidance on the coverage for telemedicine services — outside of services related to COVID-19 testing and treatment — has fallen largely to employers. In Colorado, DOI strongly encouraged employers that have self-funded health plans to comply with state and federal provisions.

Coloradans without insurance (7%): Some Colorado safety net clinics are offering telemedicine services for people without insurance, though they are not reimbursed.

Key Policy Questions Related to Reimbursement

• Does telemedicine replace in-person use of health care or add to it?

• Could increasing telehealth investment in FQHCs, RHCs, and IHS decrease the use of other types of services, such as emergency rooms?

• Will the increased use of telemedicine increase spending on health care, and if so, can Colorado afford it with a cash-strapped state budget?

• Is the telemedicine business case sound for providers? Does it create administrative headaches — like trying to collect co-pays from patients or navigating different billing rules between payers? How has it affected clinical scheduling and workflow?

• What did state agencies learn about preventing

fraud and abuse?

Research Recommendations

• Compare costs and utilization of in-person and telehealth services before the COVID-19 pandemic with utilization of telehealth services after the pandemic hit.

• Assess the degree to which safety net clinic patients used the ED for conditions that could have been potentially avoided with access to primary care. Compare to clinics that already used telehealth extensively.

• Leverage the natural experiment presented by whatever policy decision is made to compare costs and utilization before, during, and after the responses to the pandemic.

• Analyze the return on investment for health care providers by looking at revenue, expenses, margins, losses, satisfaction, quality of care, and outcomes.

Strategy #2:

Access to Services

Some providers and patients face barriers to gaining access to telemedicine.

On the provider side, most — if not all — health care organizations have expanded their telemedicine services or are implementing telemedicine quickly in response to the pandemic. This is not without challenges, especially for rural providers.

These challenges include:

• Cost of telemedicine equipment,

• Staff training and incorporating telemedicine into clinical workflow, and

• Lack of broadband access.

Access to telemedicine has pros and cons for patients. On one hand, telemedicine is convenient. It saves many patients time and money spent getting to appointments, taking time off work, and securing transportation and child care. On the other hand, accessing telemedicine from home may be challenging for patients who require language translation, who lack a private space to share sensitive health information, who are not tech savvy, or who do not have a stable internet connection.

Some providers say the decision by HCPF and DOI to allow patient visits to be conducted over the phone — rather than video chat — addresses a number of these barriers for both patients and providers.

Whether phone, video, or some other mode of telemedicine, each type has its limits. Some preventive and specialty services, like mammograms or vaccinations, simply cannot be provided remotely. Practices may need to acquire expensive telemedicine equipment such as digital medical scopes and cameras. And many communities in this large state lack the broadband to support telemedicine.

On this last point, telemedicine has shined a spotlight on the digital divide. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 11% of Colorado households — an estimated 231,028 homes — lack broadband of any type. This issue is more pronounced in the state’s rural areas, where 14% of households lack broadband compared to 10% of urban households.Mapping from the Governor’s Office of Information Technology shows wide swaths of the Eastern Plains and Western Slope without any broadband coverage.

With COVID-19, most efforts to fund and expand broadband originate with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and not the state. At the state level, the Colorado Broadband Office has established a COVID-19 website to connect providers, first responders, and others to the appropriate FCC program. If members of the general public have broadband issues, they must contact their service provider.

Key Policy Questions Related to Access

• To what extent would increasing access to telemedicine meet the health care needs of new Medicaid members in the expected enrollment surge?

• Did expanding telemedicine improve access to needed care among rural Coloradans, older adults, people with disabilities, or others who are underserved?

• To what degree have patients who frequently use ED services sought care through telehealth during the pandemic?

• What are the equity issues associated with telemedicine? To what degree do some groups of Coloradans have better or worse access to telemedicine than others?

Research Recommendations

• Analyze claims and electronic health record data to quantify any disparities in use of telemedicine services among patients with different medical conditions, complexity, and demographic and geographic characteristics prior to the telemedicine expansion and after.

• Conduct qualitative research with rural Coloradans and others facing long-standing access-to-care barriers to understand their experience accessing telemedicine services during the pandemic.

• Conduct analyses on whether other types of telehealth services — like e-consult or ECHO — improve access to care.

PROFILE: LINCOLN COMMUNITY HOSPITAL

COVID-19 Policies Accelerate a Shift to Telehealth on Eastern Plains

In Hugo, a small agricultural town on Colorado’s Eastern Plains, Lincoln Community Hospital and Care Center had just started its telehealth program when COVID-19 and the state’s stay-at-home order accelerated its plans.

Lincoln Community Hospital and Care Center averages about five patients on the floor at a time. But the hospital is connected to a care center, so staff were particularly concerned about reducing potential exposure to COVID-19.

The hospital had already begun to use telehealth for stroke patients to allow them to see Denver-based specialists remotely. Once the state’s stay-at-home order took effect, Lincoln Health, which operates the hospital, introduced a new Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant platform to allow day-to-day visits between local staff and patients to move online.

“The pandemic made us get this going as fast as possible so we could still get patients seen as a clinic patient, still have doctors seeing patients,” said Victoria Heiss, a nurse who is leading the telehealth integration program at Lincoln Health.

New regulations during COVID-19 meant that the hospital’s providers could conduct a visit from home and bill insurance, which allowed more flexibility for doctors and allowed patients to stay home and avoid risking exposure.

As of early May, about 250 patients had used Lincoln Health’s telehealth practice. Most of those visits have been conducted via video. Patients can use their smartphones to talk to their doctor.

There has been a learning curve for doctors and patients, but staff said that the technology has been, on the whole, easy to use — and could save rural residents long drives even after COVID-19-related restrictions change. “It’s great for people who don’t want to travel 90 to 100 miles to see certain doctors,” Heiss said.

Strategy #3:

Professionals

Each state oversees the licensure, certification, and rules outlining how health professionals can practice in that state. In the wake of COVID-19, Gov. Polis and state agencies like HCPF and the Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) increased the list of who can provide telemedicine services.

Figure 1 characterizes these actions in three ways: expanding the house; laying out the welcome mat; and inviting the neighbors.

The list in Figure 1 is intended to show the variety of approaches and is not intended to be exhaustive. Like the other emergency provisions, all are meant to be temporary.

State regulatory agencies stress that safeguards remain. The laws establishing the scope of services each type of professional can perform have not changed. Providers are expected to meet the same standard of care on telemedicine as they do in person. And clinicians are responsible for verifying that their malpractice insurance covers telemedicine.

The state clearly is putting a lot of trust in providers — within limits. This is perhaps best illustrated by guidance that state agencies issued about elective procedures. A March 19 executive order from Gov. Polis prohibited all elective and non-emergency procedures to curtail the spread of the virus and focus medical efforts on fighting the pandemic. In essence, the order says that the state is relying on professionals’ judgment whether a patient is in need of in-person care due to risk of worsening health or rapid deterioration.

The common denominator behind all of these approaches is that they are aimed at leveraging all available health care expertise to not only treat coronavirus, but to address other health care needs during the public health emergency.

Key Policy Questions Related to Professionals

• To what extent did disciplines like physical therapy and occupational therapy provide telemedicine services during the pandemic?

• To what extent did rules to easily reinstate expired or inactive licenses address gaps in the state’s health care workforce? Did Coloradans receive telemedicine services from out-of-state clinicians?

• What were the intended and unintended consequences of easing these professional rules?

• Are there trade-offs in cost, quality, and continuity of care between telemedicine delivered by a patient’s medical home versus a doctor-on-demand service?

Research Recommendations

• Examine claims data for the professions like PT and OT that were allowed to provide telehealth to understand the extent to which they used it.

• Use DORA data to describe the characteristics of those whose licenses were reinstated, and administrative data to understand the types of services they provided.

• Develop case studies of any key successes or adverse occurrences that came about as a result of these provisions.

PROFILE: STRIDE COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS

Dialing Up a Brand-New Telehealth Program

Before March 2020, more than 50,000 people a year walked through the doors of STRIDE Community Health Centers, a FQHC with 18 locations in the Denver metro area. STRIDE provides physical, oral, and mental health care, but telehealth has never been part of its services.

Once the pandemic hit, however, STRIDE launched a telehealth program within days. In the first week of the state’s stay-at-home order, staff got to work on the technology and operations changes necessary to offer care remotely.

“We wanted to keep sick and vulnerable patients home as much as possible and provide options for folks who prefer to receive care at home,” said Stephanie Sandhu, a family physician at STRIDE who developed the clinic’s telehealth workflows and processes.

Most telehealth visits at STRIDE have been conducted on the phone. The clinic did not have the internet bandwidth to host numerous video visits, and its electronic medical records system wasn’t integrated with a video chat platform. (STRIDE had planned to transition to a different system that allowed some video options by 2021, and it has applied for a grant to expand its bandwidth and ability to offer more video calls.)

At the beginning of April, Colorado’s Medicaid program announced that it would reimburse for these phone visits for the first time — a critical change for clinics like STRIDE, which serve mostly people who are uninsured or covered by public health programs. “We would not be where we are if that decision wasn’t made,” said Ben Wiederholt, STRIDE’s President and CEO.

While the telephone isn’t a novel technology, it has some advantages: Phone visits were more immediately accessible to many patients, who could not be introduced to a new video platform in person and, in some cases, might not have the right technology to access the platform. It was also easier for providers to connect with translation services for the clinic’s many patients who don’t speak English as a primary language. “Integrating interpretation into a video platform is very challenging,” Sandhu said. “Phone-only telehealth is so important for people who are most vulnerable – people who have language or economic barriers.”

As of late April, more than half of STRIDE’s visits were taking place remotely. STRIDE’s medical assistants were tasked with calling patients directly to check in, which allowed the clinic to stay in touch and identify who needed care immediately. Some services, like immunizations and ultrasounds, were still offered at the clinic. Providers were learning new tactics for identifying symptoms remotely, such as listening to patients’ breathing on the phone or asking patients to track their blood pressure.

As the state’s stay-at-home order lifted in early May, the clinic continued to screen patients to determine whether they need to come into the clinic. But the clinic’s staff said they hope that telephone visits can continue after the pandemic ends — maintaining a new and often effective way of connecting with the people they serve.

Strategy #4:

Information

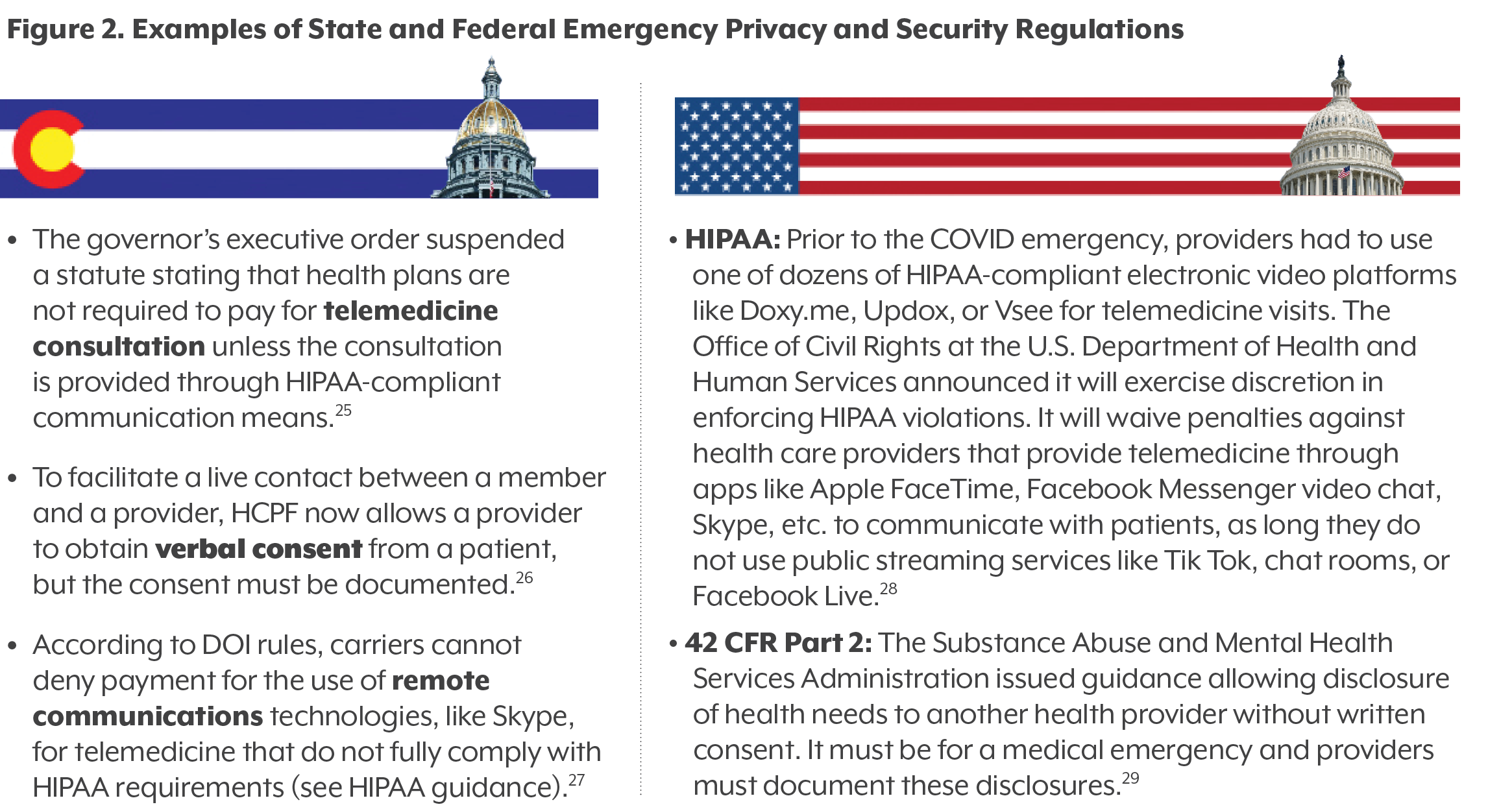

This strategy refers to the relaxation of regulations intended to protect the privacy and security of health information. The big idea: In order to accommodate social distancing restrictions and expand telemedicine during the COVID-19 emergency, the government can loosen existing regulations that encumber communication between provider and patient.

Like many of the strategies identified in this brief, the approach highlights the relationship between the federal government and the states. There are two key federal regulations that lay the foundation for protection of health information:

• HIPAA outlines what patient health information is protected and safeguards that must be in place to protect electronic information.

• Title 42, Part 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations (commonly called 42 CFR Part 2) protects patient records created by federally funded programs for substance use disorder treatment.

Colorado and other states have built upon this foundation with additional privacy and protection rules and regulations. Figure 2 displays examples of how federal and state privacy protections have been changed to facilitate greater communication between health care providers and patients.

Key Policy Questions Related to Information

• Will emergency provisions demonstrate that privacy rules in the past were too restrictive?

• Were any privacy rules standing in the way of more accessible options for care?

• Are there privacy rules that need to be tightened?

Research Recommendations

• Using provider interviews and data, assess the uptick in use of HIPAA non-compliant video platforms (like Skype) compared to HIPAA-compliant video software and audio-only telephone.

• Develop case studies and identify the extent and nature of any privacy breaches.

• Use case studies to develop quantitative approaches of surveying providers and patients about successes and challenges of using these platforms during the state of emergency.

PROFILE: PEDIATRIC PARTNERS OF THE SOUTHWEST

Telehealth Allows a Rural Practice to Stay in Touch, but Staff Worry About What’s Falling by the Wayside

At Pediatric Partners of the Southwest, in Durango, telehealth has been an established part of its health care approach for more than five years. Still, the policy changes that came with COVID-19 dramatically changed how the clinic worked.

The practice began a telehealth program in 2014 so patients could avoid having to drive 6 to 8 hours to Denver to see specialists at Children’s Hospital Colorado. It soon expanded to allow patients to have appointments with Pediatric Partners’ health care providers remotely.

Before March 2020, telehealth was mostly used for conditions that didn’t need a physical exam, like pink eye, some rashes, and some mental health visits.

By late April, most sick visits were conducted remotely through a mix of phone and video calls. The clinic is still offering some in-person check-ins, including car-side visits. The practice has focused on educating parents about when it’s important to bring their children into the office and when it’s more prudent to stay home.

“It’s been a learning curve but it’s been well received,” said Kelly Miller, a pediatrician and founder of the practice. “We’re lucky we have people in the office who can spend time teaching the family the tech steps so they’re ready when it’s time for their appointment.” Regulation changes also allowed the practice to begin using non-HIPAA-compliant video platforms like FaceTime to reach patients who did not have access to other video options.

Telehealth allowed providers to stay in touch with and offer critical care to their patients. But there are limits to its usefulness and accessibility. Some are time-worn rural phenomena: Some patients have to drive to get internet service, even if they don’t have to drive to the doctor’s office.

Others are related to policy and reimbursement. Pediatric Partners of the Southwest is a private practice but takes an unlimited number of patients with public health insurance like Medicaid. About 35% of its patients have coverage through Medicaid or Child Health Plan Plus.

While Medicaid and carriers regulated by the DOI are required to reimburse for more telehealth visits, some self-funded plans, which aren’t regulated by the state, are not reimbursing for telehealth visits, staff said.

And in Colorado, unlike in some states, preventive care visits may not be reimbursed by all payers if delivered remotely. The clinic’s overall visits have dropped between 40 and 50%.

Miller said she was worried about drops in the number of children who had been vaccinated and about the mental health of middle and high schoolers. She hoped that policies would continue to develop to allow her clinic to be reimbursed for telehealth — but was looking forward to seeing families and children in person again.

Strategy #5:

Definitions

The last strategy — redefining terms — was actually the first out of the gate.

The first two provisions of the governor’s April 1 executive order suspended the definition of “telehealth” in statute. This definition is included in the appendix on Page 18.

The result? In aligning with the governor’s executive order, and following Medicare’s lead, HCPF and DOI did two main things:

• Temporarily expanded telemedicine to allow audio-only services by telephone.

• Temporarily allowed telemedicine visits to be conducted over non-HIPAA compliant communications platforms like Skype or Facebook Messenger video.

Anecdotally, CHI’s interviews with providers have found that the audio-only phone visits are a popular mode of telehealth during the pandemic. Both patients and providers love the convenience and accessibility of simply talking on the phone.

But while the governor’s executive order redrew the line around what is officially considered “telehealth,” it did not erase the line altogether.

What was drawn in were synchronous modes of telehealth between provider and patient. In other words, communication happening in real time between a person and a clinician.

What did not make the cut? To start, communication by email and fax machine. Nor did e-consults — an asynchronous (not in real-time) mode of provider-to-provider communication and consultation. Lastly, remote provider instruction through an electronic platform like ECHO Colorado — which is often included in the spectrum of telehealth approaches — was not included.

Why did state agencies draw the line where they did?

There are a few value statements embedded in the emergency rules:

• There are limited resources and all types of telehealth cannot be included.

• The emphasis is on the patient-provider relationship and not provider-to-provider coordination.

• Addressing health needs in real time is prioritized.

These were prudent guiding principles in the wake of coronavirus. When restrictions on in-person care and non-emergency procedures are lifted, there likely will be pent-up demand and many referrals to specialty care. This presents an opportunity for the state to consider the entire spectrum of telehealth options.

Key Policy Questions Related to Definitions

• How long of a time span is necessary to answer key policy questions? Are there benefits or unintended consequences of extending the expanded definitions past the emergency expiration?

• Are some disciplines and services more amenable to telemedicine? To what extent were oral and behavioral health services provided by telehealth during the pandemic? What services are best provided through audio-only, video, or in-person modes, and will this change after the pandemic?

• Are there still services that are not covered by telemedicine reimbursement? Or for which telemedicine is not available?

• To what degree could pent-up demand for services be addressed through the spectrum of telehealth services (direct-to-consumer, asynchronous, remote patient monitoring, e-consults)?

Research Recommendations

• Compare cost, use, patient satisfaction, and provider satisfaction between practices that offered telemedicine services using a HIPAA-compliant platform vs. those who offered services through a non-HIPAA compliant platform.

• Conduct mixed methods research — qualitative and quantitative — into which services were best delivered via telemedicine during the pandemic and compare with pre- and post-pandemic data collection.

• Conduct a cross-state comparison with similar states that defined telemedicine differently or issued different guidance or regulations.

• Explore a pilot program to test the impact of provider-to-provider electronic consultations on specialty care access, use, and expenditures.

Final Thoughts: Telehealth’s Evolving Evidence

Colorado’s RAPID response of temporarily expanding some telemedicine regulations related to reimbursement, access, professionals, information, and definitions during the pandemic is necessary, prudent, and appropriate. It aligns with the approaches taken by many other states and by federal agencies. And judging by the way the health system swiftly adapted, the approach seems to be meeting the objectives of keeping patients and providers safe and secure while attempting to improve access to care.

Big policy decisions lie ahead in telemedicine’s next episode, namely whether to continue the emergency provisions that have greatly expanded its use. These decisions will require evidence of how well the provisions worked.

This paper identifies key policy questions about the state’s telemedicine approach. It all comes down to the quadruple aims of lowering costs while improving health and maintaining a quality experience for the patient and provider. The cost part could be a kicker: The state will be learning to do more with less in the wake of an economic downturn resulting in less state revenue.

The keys are thoughtful deliberation, targeted research, and meaningful evaluation. Research must keep up with constantly evolving telehealth technology and determine the return on investment of emerging innovations like e-consults. And analysis of Colorado’s experience before and during the pandemic will inform the state’s policy direction. It is the evidence that will determine whether telehealth in Colorado goes back to the future.

Five Key Resources

This brief does not contain an exhaustive list of state and federal regulations and guidance on

telehealth and telemedicine. Nor should it be construed as advice on legal or compliance issues.

For more information, start with these five Colorado sources:

• CDPHE Provider Page: https://covid19.colorado.gov/telehealth-for-providers

• Office of the Governor, Executive Orders: https://www.colorado.gov/governor/2020-executive-orders

• Office of e-Health Innovation (OeHI): https://www.colorado.gov/OeHI

• HCPF Telemedicine for Providers: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/provider-telemedicine

• DORA (DOI): https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/dora/covid-19-and-insurance