STORY ONE: Mental Health Challenges Are a Risk Factor for Suicide — But Many Go Untreated

Many people who have died by suicide in Colorado were reported as having a current depressed mood or a diagnosed mental health problem like depression, anxiety, or other conditions such as schizophrenia. But less than a third were identified as currently receiving mental health care.

As a state, Colorado has a higher prevalence of mental health issues and lower rates of access to care, according to Mental Health America’s 2021 State of Mental Health in America report. Colorado has an overall ranking of 47 out of 50 states and the District of Columbia, based on account 15 measures of mental health and substance use prevalence among adults and youth as well as access to care.

Access to mental health care remains a persistent challenge in Colorado: More than one in 10 Coloradans reported not getting needed treatment for mental health issues in 2019, according to the Colorado Health Access Survey. The number of suicide deaths where a current diagnosed mental health problem was reported has increased over time, but gaps in treatment persist.

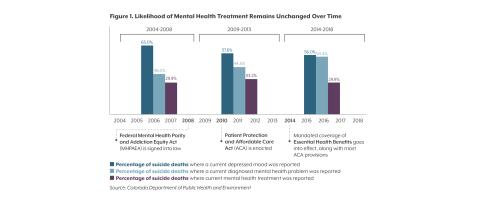

Policy changes aimed at improving access to mental health care may be partly responsible for the increase in diagnosis (see Figure 1): Between 2004-2008, prior to the implementation of key legislation like the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which improved insurance coverage for mental health care, 38.0% of people who died by suicide in Colorado had a reported current diagnosed mental health problem. After implementation of these policies, the rate increased to more than half (54.4% between 2014-2018). This likely reflects more people having access to at least an initial appointment with a mental health provider, or more awareness of mental health challenges on the part of primary care providers.

Yet the number of people who died by suicide who were reported as receiving current mental health treatment has remained stubbornly unchanged at less than a third.

The 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey found that cost and coverage were the largest barriers for people who didn’t get needed mental health services. A survey conducted by Gov. Jared Polis’ Behavioral Health Task Force echoed these findings, with 92% of respondents reporting concerns with access to care.

Policymakers are looking for ways to further improve access: The Task Force’s recently-released Blueprint for Behavioral Health Reform outlines steps to build a stronger system of care through addressing workforce shortages, improving affordability, and streamlining the system to ensure Coloradans can get care when they need it.

STORY TWO: Structural Racism Perpetuates Worse Health Outcomes Among People of Color

People of color in Colorado who died by suicide were less likely to have mental health treatment than white Coloradans, even though similar percentages of all groups were reported as having a current depressed mood (see Figure 2).

Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, and Native American people experience higher rates of some mental health conditions, and yet they face disproportionately greater difficulties in accessing care than white people in Colorado. It is not race or ethnicity that inherently causes these disparities or perpetuates inequities, but structural racism and the differential access to services or opportunities by race, such as in the health care system. The 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, which gives an overview of health care received in the U.S., found that compared to white patients, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander groups received worse care for 40% of the quality measures studied.

Exclusion and discrimination can also act as stressors (see: Systemic Racism and Health) and can manifest in the health care system through issues like lack of workforce diversity.

The behavioral health care system is already facing an overall workforce shortage, but even fewer providers offer culturally and linguistically competent care for people of color. The demand for psychologists among non-white racial and ethnic groups is expected to grow by 24% from 2015 to 2030. While people of color make up about 28% of the nation’s population, in 2015, only 14% of psychologists in the U.S. workforce were non-white.

Cultural beliefs and stigma related to mental health can also lead people to avoid care. Understanding and addressing this is important to ensuring culturally responsive care. But if there are few providers from diverse backgrounds or a lack of training in these issues for current providers, inequities in access to care and quality of care will persist (see: Stigma and Protective Factors).

There are national efforts to create a more diverse behavioral health workforce, such as the Minority Fellowship Program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The program aims to improve behavioral health care outcomes across racial and ethnic groups by increasing the number of people with diverse backgrounds in the field, and by improving the cultural competency of existing health care providers. Additionally, many groups have created mental health provider directories to help people find therapists and support from providers with whom they identify. Colorado’s Office of Suicide Prevention recently released a draft statement and action plan that acknowledges the office’s role, commitment, and ability to dismantle racism and apply a racial equity lens to its work.