Stable housing is associated with better health. Coloradans lacking stable housing are more likely to report poor physical, mental, and oral health.

Yet some 360,000 Coloradans (6.7%) were worried they would not have a stable place to live in the next two months in 2019, according to new data from the Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS). That is one in every 15 residents.

The cost of housing affects people’s ability to afford other necessities, including food and health care. More than half of Coloradans who reported housing instability (54.2%) had problems paying for food, compared with 6.1% who did not report housing instability. And of those without stable housing, 51.9% reported experiencing a problem paying a medical bill, versus just 15.4% of those with stable housing.

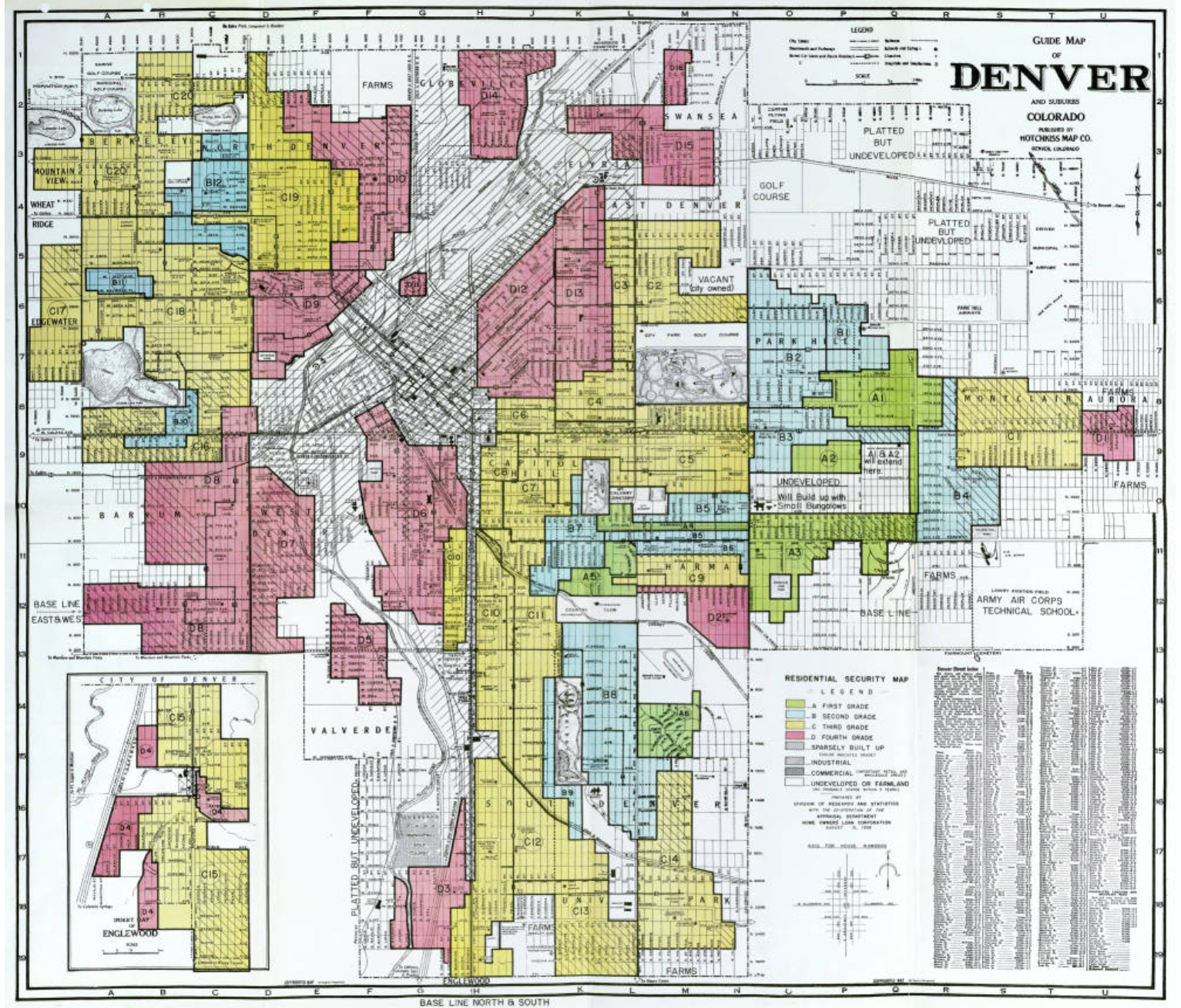

The CHAS offers insight into the communities and regions where housing instability is particularly common. While housing instability affects Coloradans from all walks of life, the CHAS suggests that those with lower incomes, people living in some rural communities, millennials, and people of color are particularly likely to experience instability.