Coloradans’ mental well-being took a turn for the worse during the COVID-19 pandemic, and people who lost their jobs were especially likely to report poor mental health.

One in four respondents (23.7%) to the 2021 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) reported poor mental health — a jump of more than 8 percentage points since 2019. Meanwhile, almost half of people who lost their jobs during the pandemic reported poor mental health (44.4%). They were also more likely to report that their general health was worse than those who did not lose their jobs. What’s more, this disparity persisted even for people who got a new job.

In the wake of the pandemic, Colorado’s political leaders are contemplating a variety of large investments in mental health. These findings suggest that people who lost their jobs during the pandemic merit special attention — even those who found work after they were laid off.

Background

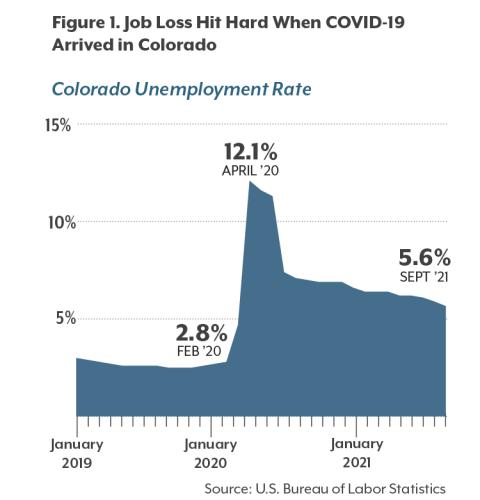

When COVID-19 began spreading in Colorado in spring 2020, many people ceased going to stores and restaurants to minimize their exposure to the virus. Local and state orders limited the number of people who could be in a business, and indoor dining at restaurants was banned for a time.

As a result, large sectors of the economy shut down, including dining, tourism, retail, and others. Half a million Coloradans lost their jobs during the pandemic, according to the CHAS. Most of the job loss occurred in March and April 2020, when the state’s unemployment rate rocketed from 2.8% to 12.1% (see Figure 1).

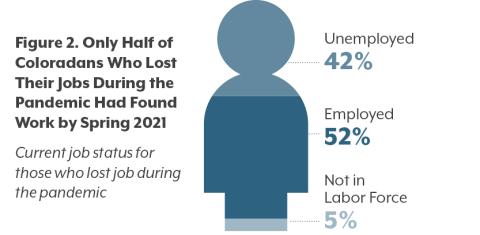

Four in 10 people (42.2%) who lost their jobs because of COVID were still unemployed and looking for work as of the day they answered this survey, which was fielded from February to June 2021. About 5% left the workforce entirely (see Figure 2).

Job Loss and Health: A Striking Connection

Employment is closely tied to health, and losing a job can affect numerous aspects of a person’s life.

Physical Health: Jobs provide the means to pay for the things that help us stay healthy and are often a source of more affordable, higher-quality health insurance than people can get by buying directly from an insurance company.

Mental Health: Employment is more than a job. It can provide community, personal dignity, and self-determination, which improve mental health.

Economic Health: Income provides the means for housing, nutrition, necessities, and the things that provide comfort, like a weekend in the mountains, birthday presents for the kids, or a date night dinner.

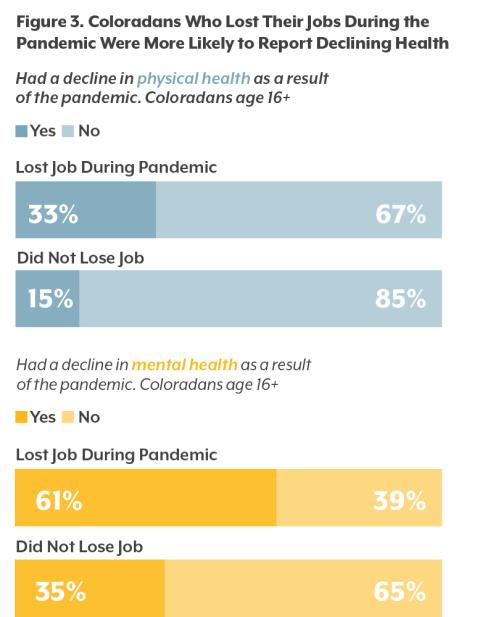

The CHAS asked if people’s mental and physical health declined during the pandemic. Respondents who had lost their jobs were nearly twice as likely to say their health had declined (see Figure 3). A third of people who lost their jobs said their physical health suffered, compared with just 15% of those who didn’t lose their jobs. And 61% of those who lost their jobs said their mental health declined as a result of COVID, compared with 35% of those who didn’t lose their jobs.

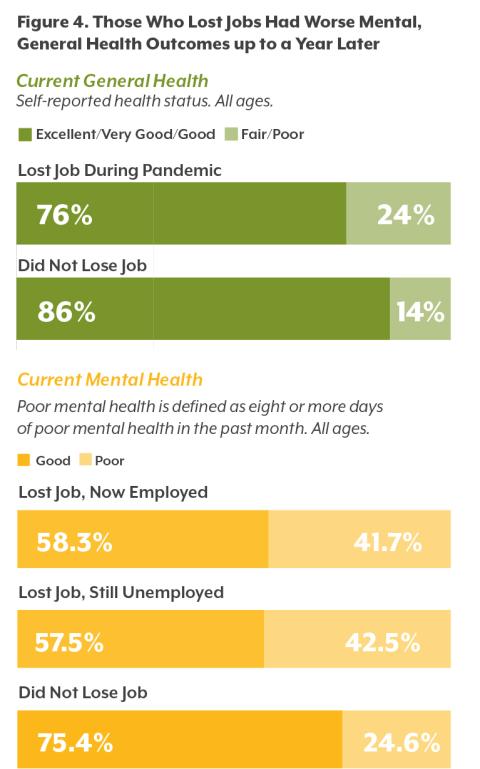

The survey also asked people about the state of their mental health in the previous 30 days and the current state of their general health. When people said they experienced eight or more days of poor mental health in the past month, the survey counted them as having poor mental health (see Figure 4).

A year after the wave of layoffs, people who had lost their jobs — even those who had since found a new one — were still reporting worse mental and general health than those who had kept their jobs. More than 40% of people who lost their jobs during the pandemic reported their mental health as poor, and the percentage was statistically the same for those who had found new work and those who were still unemployed.

Many people who lost their jobs because of COVID were already at higher risk of poor health because they had lower incomes or faced systemic discrimination and other factors. The Colorado Health Access Survey itself cannot prove that COVID-related job loss caused health declines. However, other research has shown a clear causal connection between job loss and declining mental and physical health.

Layoffs Hit Hardest for Young People and People of Color

People who had the fewest advantages in the job market before the pandemic were most likely to lose their jobs when COVID-19 arrived.

American Indian/Alaska Native and Black or African American Coloradans were three times more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic than white Coloradans — a reflection of the discriminatory systems that have kept them from prospering economically. People with the lowest wages were twice as likely to lose their jobs as those making four times the poverty level. And young adults were much more likely than those 30 or older to lose their jobs (see Figure 5).

Policy Implications: Targeting Support

This brief demonstrates the close ties between health and job loss. However, public policies and systems still tend to address these factors separately. For example, the Colorado legislature has set aside about $2 billion in federal stimulus money in three realms: behavioral health, housing, and economic development. Separate committees are making recommendations for each topic. When legislators return in January 2022 to allocate the money, they should consider the intertwined effects these factors have on each other.

For example, workforce centers could be funded to perform more outreach and assessments of mental health. Unemployment insurance payments could provide another touchpoint to ask people if they could use mental health assistance. And employers could be trained to recognize signs of poor health in new workers they bring on board.

Half a million Coloradans lost their jobs in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic — about 10% of the state population. By spring 2021, half of those who had lost their jobs had found new ones. But their stories do not end there. The sudden job loss damaged many people’s mental and physical health, and the CHAS shows that getting a new job was not necessarily a cure. A substantial portion of Coloradans suffered the effects of job loss, and policymakers should give their well-being special attention as state and local governments continue to guide the economic recovery.

About the CHAS

The Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) is the premier source of information about health insurance coverage, access to health care, use of health care services, and the social factors that influence health in Colorado. The biennial survey of more than 10,000 households has been conducted since 2009. Survey data are weighted to reflect the demographics and distribution of the state’s population. The 2021 CHAS was fielded between February 1 and June 7, 2021. The survey was conducted in English and Spanish. New questions were added to the 2021 survey to capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the impact of telehealth, social factors, and other topics. Visit colo.health/CHAS21 for information on the 2021 CHAS and our generous sponsors.

2021 Sponsors