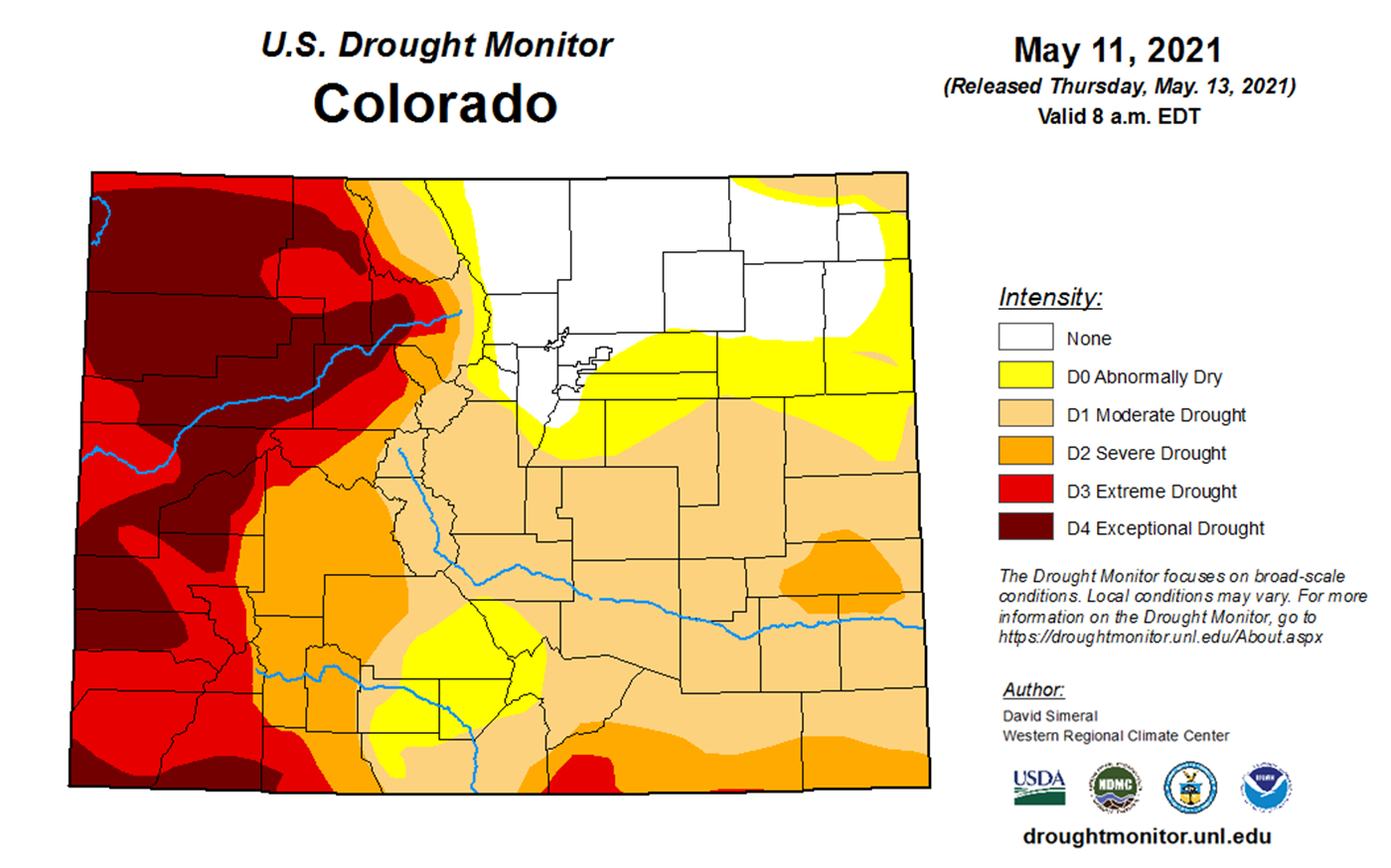

Recent headlines have touted how well parts of Colorado are faring in terms of snow and rainfall, and the latest round of gray skies and drizzle have provided additional reasons for optimism. While the past few weeks have been encouraging, there likely has not been enough precipitation to prevent another summer of heat-related challenges.

As Colorado enters its 20th year of drought, longer fire seasons and increasingly warm temperatures are top of mind for state and local governments as they engage in a delicate balancing act of trying to mitigate the impacts of climate change while adapting to a warmer and drier Colorado.

The state is expecting a continuation of hot and dry conditions this year – resulting in predictions of higher-than-normal potential for large fires.

Both wildfire and drought are natural in our state, but rising temperatures are driving natural events to extreme levels. These climate-related impacts negatively affect the environment and human health, especially for sensitive populations such as older adults, young children, and low-income communities. CHI has highlighted the connection between climate change and health in two reports: Colorado’s Climate and Colorado’s Health and Global Issue, Local Risk.

Colorado’s New Normal: What to Expect in 2021

Wildfire

Colorado used to have two distinct fire seasons. The first was from late May to early July and the second was from late August through September. But recently, those seasons have been extended to a full calendar year, according to the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control.

Yearly wildfire predictions rely on historical trends – and those trends signal an above average fire year in 2021. The core fire season is now an average of 78 days longer than it was in the 1970s, and since the 1990s, fires have become larger and more intense. Additionally, 20 of the worst wildfires in Colorado history have occurred since 2000, and the three largest occurred just last year (see Figure 1).

These large fires can bring destruction to communities and can also produce harmful smoke that irritates people’s chests, lungs, and hearts.